Rottweiler Health

There are several health issues connected with the Rottweiler, and some are listed below:

- Aortic Stenosis

- Hip Dysplasia

- Elbow Dysplasia

- Entropion

- Ectropion

- Cruciate Ligament Rupture

- OCD (Osteochondritis Dessicans)

- Cancer

- JLLP (Juvenile Laryngeal Paralysis & Polyneuropathy)

- Wet Eczema

- Cold Water Tail

Aortic Stenosis

This is due to a partial obstruction to the flow of blood as it leaves the left side of the heart (the left ventricle) through the main blood vessel (the aorta) that carries blood to the rest of the body. Due to the obstruction the heart must work harder to pump adequate blood. Clinical signs depend on the degree of the narrowing. Some puppies have what are called “innocent” murmers which disappear. Others need further investigation. There are tests for this condition – an Auscultation (stethoscope) ECG, and more extensive investigations such as Doppler echocardiography and chest x-rays. These should be carried out by qualified Cardiologists (e.g. SAC veterinary surgeons) who can issue a certificate. In its mildest form there are no problems for the dog, but it may still be passed on to its offspring.

Recommendation is that no affected animals are used for breeding.

Some breeders are now Heart Testing their breeding animals through the BVA Scheme. This is a quick and painless test done by a qualified cardiologist vet. Electrodes are attached to the dog’s skin and a paper read-out is produced (just the same as a human’s heart test). A certificate is given to the owner stating whether the heart was Normal or Abnormal and only those animals who receive a Normal reading should be bred from.

Below you can read a full report from John Sauvage, Veterinarian from Pierson Stewart & Partners of Cranbrook, Kent.

Recommendation is that no affected animals are used for breeding.

Some breeders are now Heart Testing their breeding animals through the BVA Scheme. This is a quick and painless test done by a qualified cardiologist vet. Electrodes are attached to the dog’s skin and a paper read-out is produced (just the same as a human’s heart test). A certificate is given to the owner stating whether the heart was Normal or Abnormal and only those animals who receive a Normal reading should be bred from.

Below you can read a full report from John Sauvage, Veterinarian from Pierson Stewart & Partners of Cranbrook, Kent.

| Sub Aortic Stenosis report by John Sauvage.pdf | |

| File Size: | 1682 kb |

| File Type: | |

Hip Dysplasia

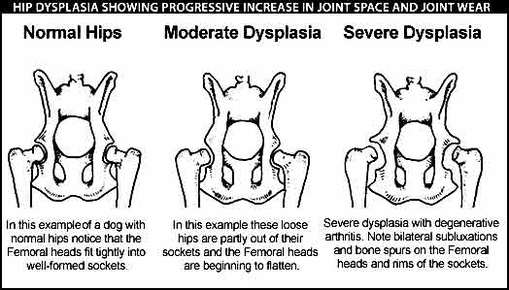

Hip dysplasia is the most common inherited orthopaedic disease in large and giant breed dogs, and occurs in many medium-sized breeds as well. The hip joint is a “ball and socket” joint; the “ball” (the top part of the thigh bone or femur) fits into a “socket” (acetabulum) formed by the pelvis. If there is a loose fit between these bones, and the ligaments which help to hold them together are loose, the ball may slide part way out of the socket (subluxate). The mode of inheritance is polygenic (caused by many different genes). Scientists do not yet know which genes are involved, or how many genes. Factors that can make the disease worse includes excess weight, a fast growth rate, and high-calorie or supplemented diets.

X-rays are taken when the dog is over one year old, then the x-rays are sent to the BVA for scoring. The hip-scoring system warrants explanation as it is quite confusing for the uninitiated. The score is determined by allocating points to each imperfection on the ball and socket of each hip joint. The minimum (best) score for each hip is 0, while the maximum (worst) is 53, making a total of 106 when multiplied by two for both hips. Basically: the higher the score, the more likelihood of Hip Dysplasia developing.

X-rays are taken when the dog is over one year old, then the x-rays are sent to the BVA for scoring. The hip-scoring system warrants explanation as it is quite confusing for the uninitiated. The score is determined by allocating points to each imperfection on the ball and socket of each hip joint. The minimum (best) score for each hip is 0, while the maximum (worst) is 53, making a total of 106 when multiplied by two for both hips. Basically: the higher the score, the more likelihood of Hip Dysplasia developing.

The hip scores should be well within the average (mean) score for the breed, which, currently, is 13 for the Rottweiler. The BVA advise that breeders wishing to try to control HD should breed only from animals with hip scores below the breed mean score. So, if the parents of your puppy have scores below 13, then that would be an indication that your puppy should have sound hips. If the parents had a score of 0:0 then that would be perfect scores! You should look for scores as even as possible e.g. you don’t want an uneven number such as 1:12, as this could indicate a problem in one hip. If possible, try to ascertain the scores of the ancestors of the puppy’s parents. Some breeders note these on the animal’s pedigree.

The recommendation is to breed from the lowest hip scores, the Rottweiler Club Code of Ethics for members states that the highest score which can be bred from is 16, with no more than 8 on either hip.i.e. 8/8. The lower the score the better. The disease is progressive.

For further information about the Hip Dysplasia Scheme for dogs from the BVA (British Veterinary Association) please follow the link: BVA Hip Scheme

The recommendation is to breed from the lowest hip scores, the Rottweiler Club Code of Ethics for members states that the highest score which can be bred from is 16, with no more than 8 on either hip.i.e. 8/8. The lower the score the better. The disease is progressive.

For further information about the Hip Dysplasia Scheme for dogs from the BVA (British Veterinary Association) please follow the link: BVA Hip Scheme

Elbow Dysplasia

Elbow dysplasia has been identified as a significant problem in many breeds. Importantly, the condition appears to be increasing worldwide. It begins in puppy-hood, and can affect the dog for the rest of its life.

Since the late 1960s, veterinary surgeons routinely dealing with lame dogs have been aware of an increasing number of problems which arise during puppyhood. Hip dysplasia was the first disease to be widely recognised, and a scheme to assess and control it is well established. More recently, elbow dysplasia (ED) has been identified as a significant problem in many breeds. Importantly the condition appears to be increasing worldwide and, although the disease begins in puppyhood, it can affect the dog for the rest of its life.

The term elbow dysplasia refers to several conditions that affect the elbow joint; osteochondrosis of the medial humeral condyle, fragmented medial coronoid process, ununited anconeal process and incongruent elbow. More than one of these conditions may be present, and this disease often affects both front legs. This is a polygenic condition, although it is not currently known how many or which genes are responsible. Environmental factors such as over-feeding, which causes fast weight gain and growth can also affect the development of this condition in dogs that are genetically predisposed to it.

The scoring system is totally different from the hip scoring system, and can be quite baffling. The grades for each elbow are not added together as they are for the two hips in the hip dysplasia scheme. Two x-rays are taken of each elbow and the grading system is simple:

Grade Description

0 Normal

1 Mild ED

2 Moderate ED or a primary lesion

3 Severe ED

The overall grade given for both elbows is the grade that was given to the elbow with the highest score. The lower the grade the less the degree of elbow dysplasia evident on the x-ray. It is recommended by the BVA [British Veterinary Association] that those who score 2 and over are not used for breeding. Another source advises that dogs who produce the condition should not be used for breeding again.

THE ONLY WAY TO DETERMINE HIP and ELBOW STATUS IS BY X-RAY

Dogs which have clinical ED often become lame between six and 12 months of age. Initially the lameness may be difficult to ascribe to a particular joint. However, at this age a persistent forelimb lameness should be investigated by a veterinary surgeon. There are other conditions leading to signs similar to those of ED so the veterinary surgeon needs to consider these as well. Diagnosis of ED is normally based on a forelimb lameness with pain on flexion or extension of the elbow. The animal may have a short or stilted forelimb gait as both elbows are often affected. Confirmation of the diagnosis is made by finding primary or secondary lesions on radiographs of the elbow.

Treatment methods vary depending on the nature and severity of the problem. Conservative treatment involving weight restriction and control of exercise is always important. Drugs may be used to relieve the pain and inflammation associated with the condition and to promote repair processes within the joint. In some dogs, surgery is required to remove fragments of cartilage and bone from the joint to relieve pain, but this is not always appropriate. In nearly all the cases there are some secondary changes which lead to some problems with the joint throughout life, possibly restricting the dog's ability to exercise. However, most dogs will be comfortable with a fair level of exercise if treated carefully between the ages of six and 18 months.

For a more detailed look into Elbow Dysplasia, please download the PDF.

For further information about the Elbow Dysplasia Scheme for dogs from the BVA (British Veterinary Association) please follow the link: BVA Elbow Scheme

Since the late 1960s, veterinary surgeons routinely dealing with lame dogs have been aware of an increasing number of problems which arise during puppyhood. Hip dysplasia was the first disease to be widely recognised, and a scheme to assess and control it is well established. More recently, elbow dysplasia (ED) has been identified as a significant problem in many breeds. Importantly the condition appears to be increasing worldwide and, although the disease begins in puppyhood, it can affect the dog for the rest of its life.

The term elbow dysplasia refers to several conditions that affect the elbow joint; osteochondrosis of the medial humeral condyle, fragmented medial coronoid process, ununited anconeal process and incongruent elbow. More than one of these conditions may be present, and this disease often affects both front legs. This is a polygenic condition, although it is not currently known how many or which genes are responsible. Environmental factors such as over-feeding, which causes fast weight gain and growth can also affect the development of this condition in dogs that are genetically predisposed to it.

The scoring system is totally different from the hip scoring system, and can be quite baffling. The grades for each elbow are not added together as they are for the two hips in the hip dysplasia scheme. Two x-rays are taken of each elbow and the grading system is simple:

Grade Description

0 Normal

1 Mild ED

2 Moderate ED or a primary lesion

3 Severe ED

The overall grade given for both elbows is the grade that was given to the elbow with the highest score. The lower the grade the less the degree of elbow dysplasia evident on the x-ray. It is recommended by the BVA [British Veterinary Association] that those who score 2 and over are not used for breeding. Another source advises that dogs who produce the condition should not be used for breeding again.

THE ONLY WAY TO DETERMINE HIP and ELBOW STATUS IS BY X-RAY

Dogs which have clinical ED often become lame between six and 12 months of age. Initially the lameness may be difficult to ascribe to a particular joint. However, at this age a persistent forelimb lameness should be investigated by a veterinary surgeon. There are other conditions leading to signs similar to those of ED so the veterinary surgeon needs to consider these as well. Diagnosis of ED is normally based on a forelimb lameness with pain on flexion or extension of the elbow. The animal may have a short or stilted forelimb gait as both elbows are often affected. Confirmation of the diagnosis is made by finding primary or secondary lesions on radiographs of the elbow.

Treatment methods vary depending on the nature and severity of the problem. Conservative treatment involving weight restriction and control of exercise is always important. Drugs may be used to relieve the pain and inflammation associated with the condition and to promote repair processes within the joint. In some dogs, surgery is required to remove fragments of cartilage and bone from the joint to relieve pain, but this is not always appropriate. In nearly all the cases there are some secondary changes which lead to some problems with the joint throughout life, possibly restricting the dog's ability to exercise. However, most dogs will be comfortable with a fair level of exercise if treated carefully between the ages of six and 18 months.

For a more detailed look into Elbow Dysplasia, please download the PDF.

For further information about the Elbow Dysplasia Scheme for dogs from the BVA (British Veterinary Association) please follow the link: BVA Elbow Scheme

| Elbow Dysplasia.pdf | |

| File Size: | 188 kb |

| File Type: | |

Entropion

Entropion is a rolling inwards of the eyelids causing the eyelashes to rub on the surface of the eye. This is particularly distressing and painful to the dog and results in damage to the cornea, causing ulcers. There are degrees of Entropion ranging from a slight inrolling to a more serious case requiring surgical correction.

Ectropion

Ectropion is a rolling outwards of the eyelids which usually resolves as the dog grows and matures. It may predispose to conjunctivitis but is usually cosmetic and rarely requires corrective surgery.

BOTH CONDITIONS ARE INHERITED

BOTH CONDITIONS ARE INHERITED

Cruciate Ligament Rupture

These are the ligaments which cross-over behind the kneecap, holding the top and bottom parts of the hind legs together (i.e. femur and tibia\fibula). These ligaments can sometimes rupture or stretch; sometimes they snap completely rendering the dog severely lame. They can be fixed with surgery. Although considered to be partly hereditary through straight angulation in the hindquarters, contributory factors towards this common condition include: size [height], obesity, muscular and ligament laxity, uncontrolled exercise, turning suddenly and sharply, getting legs caught in rabbit holes or jumping fences, etc.

Give a Dog a Genome (GDG) Project & its role in Cruciate Ligament research

A Rottweiler with a Cruciate Ligament Injury was selected by the Animal Health Trust (Reg Charity No 209642) to be whole genome sequenced as part of Give a Dog a Genome (GDG). The sequencing has now been completed by the external laboratory and the data has been made available for us to download.

What happens next?

The amount of data generated for each sample is enormous, around 80-90 Gb. To put that into perspective, data from only 10 dogs will fill up the average modern personal computer, and the processing of the data will use the full capacity of the computer for months. As a result it takes time (about 1 week) and a great deal of computing power to download and process the data so that it is ready for analysis. Once this stage has been completed, the Rottweiler Cruciate Ligament Injury data will be ready for further analysis.

The data will be added to the genome bank, and will begin contributing to studies in other breeds immediately. In addition, the data will be made available to other scientists for use in their own studies, and the Rottweiler breed has therefore made a vital contribution to genetic research affecting the welfare of dogs worldwide.

As Prof Peter Muir at the University of Wisconsin is already working on Rottweiler with Cruciate Ligament Injury, we feel that the best use of the data is to share it with Peter Muir to add to their existing data. Analysis of the data to attempt to identify any variants that contribute to Cruciate Ligament Injury in Rottweiler will therefore not be conducted by the GDG team at the AHT. However, we do expect that Peter Muir will inform is of any relevant findings, which will then be passed on.

AHT would like to pass on their thanks to the breed community for participating in Give a Dog a Genome. Further updates will be posted as they become available.

What happens next?

The amount of data generated for each sample is enormous, around 80-90 Gb. To put that into perspective, data from only 10 dogs will fill up the average modern personal computer, and the processing of the data will use the full capacity of the computer for months. As a result it takes time (about 1 week) and a great deal of computing power to download and process the data so that it is ready for analysis. Once this stage has been completed, the Rottweiler Cruciate Ligament Injury data will be ready for further analysis.

The data will be added to the genome bank, and will begin contributing to studies in other breeds immediately. In addition, the data will be made available to other scientists for use in their own studies, and the Rottweiler breed has therefore made a vital contribution to genetic research affecting the welfare of dogs worldwide.

As Prof Peter Muir at the University of Wisconsin is already working on Rottweiler with Cruciate Ligament Injury, we feel that the best use of the data is to share it with Peter Muir to add to their existing data. Analysis of the data to attempt to identify any variants that contribute to Cruciate Ligament Injury in Rottweiler will therefore not be conducted by the GDG team at the AHT. However, we do expect that Peter Muir will inform is of any relevant findings, which will then be passed on.

AHT would like to pass on their thanks to the breed community for participating in Give a Dog a Genome. Further updates will be posted as they become available.

OCD (Osteochondritis Dessicans)

OCD is a general term given to problems which occur most commonly in the joint areas, i.e. elbows, shoulders and hocks. Problems usually start in young dogs at around 4-6 months of age. The growth of the bone ends can be faulty because they do not grow at the same time or are mis-shapen and are therefore not always covered by synovial fluid. As bones grow they can sometimes split, and small pieces of bone dislodge into the joint space, causing ulceration and pain. This can be intermittent and uncomfortable and would be rather like having a stone in your shoe. Sometimes the joints simply do not fit together properly. These problems can be detected by x-ray and to some degree can be corrected by surgery, but this is not always successful.

Cancer

This ugly, insidious disease has, unfortunately, been reported in far too many Rottweilers. It occurs in many areas of the dog but the most common examples are lymphoma (cancer of the lymph glands); bone, liver and spleen; and many other malignant lumps. It has not been established whether there is an hereditary link or whether feedstuffs, vaccinations or lifestyle can be a contributory factor.

Bone Cancer in Rottweilers

Osteosarcoma is a malignant bone tumour, which at present sadly represents a fatal progressive condition in the majority of affected dogs. This generally presents with affected dogs becoming lame, sometimes significantly so and often a painful swelling develops in the affected bone. The lameness may be subtle at first however can suddenly worsen as the affected region of the bone suffers a fracture. Although commonly occurring on the limbs, these tumours can also arise in other sites including the bones of the skull, in the nasal cavity, the jawbone, ribs and hip bones.

Unfortunately in many dogs, particularly Rottweilers that are very tolerant of orthopaedic pain, this tumour only becomes obvious at a late stage. This limits the ability of Veterinary Surgeons to improve their quality of life and their survival time is unfortunately limited. This factor is a major drive to developing earlier methods of diagnosis to improve our ability as Vets to treat this disease successfully.

A number of breeds are suspected of having a higher incidence of Osteosarcoma. The majority of these are giant breeds and include Irish Wolfhounds, Great Danes, Saint Bernards and Rottweilers. A number of factors are thought to influence the development of Osteosarcoma and include early neutering, body weight and height. There are a number of genes and molecules that have been shown to increase the risk of developing this disease. Some of these also influence its aggressiveness and ability to spread and to enable it to persist and resist treatment. A number of these have been shown in small studies to be present in Rottweilers. As Rottweilers are suggested to be at an increased risk of developing Osteosarcoma it is very important for us to determine whether there is a clear genetic predisposition amongst Rottweilers in the UK. The identification of underlying genetic susceptibility will lead to improvements in our ability to diagnose and treat this disease at an earlier stage.

At the University of Nottingham, research is already underway into discovering more about this disease (along with other types of canine and feline cancer). Importantly, being able to determine whether an animal might develop a disease in the future is of great benefit. Should this information be known, those factors that are recognised to increase the potential for development of this tumour can be minimised and the disease may not develop.

We are already investigating particular characteristics of Osteosarcoma in Rottweilers by liaising with histology laboratories and veterinary surgeons throughout the UK. This will help determine the true prevalence of this tumour in the breed and enable us to determine more about its behaviour and development along with factors that seem to be influencing this. Much of the work into Osteosarcoma in Rottweilers has been undertaken in the USA and this new study may therefore provide interesting and different information.

In 2013 The Rottweiler Club were honoured to be approached by The University of Nottingham regarding the research Project into Osteosarcoma in Rottweilers. The research project involved Rottweiler owners and breeders taking part by completing a questionnaire and providing simple, painless cheek swabs from their dogs to help gather data genetic material to analyse and give insight into the causes of osteosarcoma in Rottweilers and to have more knowledge to help fight and eliminate the deadly disease for the future of our Rottweilers.

Samples were taken from many Rottweilers to investigate genetic influences in Osteosarcoma development. This includes not only those dogs that are affected by the disease but also those that are not. These samples were then analysed using sophisticated genetic techniques to determine if there are were any common features in all or some of these animals. The research is ongoing and it is hoped we will be able to discover genes or abnormal areas of particular genes that might represent an increased risk.

Bone Cancer in Rottweilers

Osteosarcoma is a malignant bone tumour, which at present sadly represents a fatal progressive condition in the majority of affected dogs. This generally presents with affected dogs becoming lame, sometimes significantly so and often a painful swelling develops in the affected bone. The lameness may be subtle at first however can suddenly worsen as the affected region of the bone suffers a fracture. Although commonly occurring on the limbs, these tumours can also arise in other sites including the bones of the skull, in the nasal cavity, the jawbone, ribs and hip bones.

Unfortunately in many dogs, particularly Rottweilers that are very tolerant of orthopaedic pain, this tumour only becomes obvious at a late stage. This limits the ability of Veterinary Surgeons to improve their quality of life and their survival time is unfortunately limited. This factor is a major drive to developing earlier methods of diagnosis to improve our ability as Vets to treat this disease successfully.

A number of breeds are suspected of having a higher incidence of Osteosarcoma. The majority of these are giant breeds and include Irish Wolfhounds, Great Danes, Saint Bernards and Rottweilers. A number of factors are thought to influence the development of Osteosarcoma and include early neutering, body weight and height. There are a number of genes and molecules that have been shown to increase the risk of developing this disease. Some of these also influence its aggressiveness and ability to spread and to enable it to persist and resist treatment. A number of these have been shown in small studies to be present in Rottweilers. As Rottweilers are suggested to be at an increased risk of developing Osteosarcoma it is very important for us to determine whether there is a clear genetic predisposition amongst Rottweilers in the UK. The identification of underlying genetic susceptibility will lead to improvements in our ability to diagnose and treat this disease at an earlier stage.

At the University of Nottingham, research is already underway into discovering more about this disease (along with other types of canine and feline cancer). Importantly, being able to determine whether an animal might develop a disease in the future is of great benefit. Should this information be known, those factors that are recognised to increase the potential for development of this tumour can be minimised and the disease may not develop.

We are already investigating particular characteristics of Osteosarcoma in Rottweilers by liaising with histology laboratories and veterinary surgeons throughout the UK. This will help determine the true prevalence of this tumour in the breed and enable us to determine more about its behaviour and development along with factors that seem to be influencing this. Much of the work into Osteosarcoma in Rottweilers has been undertaken in the USA and this new study may therefore provide interesting and different information.

In 2013 The Rottweiler Club were honoured to be approached by The University of Nottingham regarding the research Project into Osteosarcoma in Rottweilers. The research project involved Rottweiler owners and breeders taking part by completing a questionnaire and providing simple, painless cheek swabs from their dogs to help gather data genetic material to analyse and give insight into the causes of osteosarcoma in Rottweilers and to have more knowledge to help fight and eliminate the deadly disease for the future of our Rottweilers.

Samples were taken from many Rottweilers to investigate genetic influences in Osteosarcoma development. This includes not only those dogs that are affected by the disease but also those that are not. These samples were then analysed using sophisticated genetic techniques to determine if there are were any common features in all or some of these animals. The research is ongoing and it is hoped we will be able to discover genes or abnormal areas of particular genes that might represent an increased risk.

|

Thank you to Dr Mark Dunning, Clinical Associate Professor in Small Animal Internal Medicine at the School of Veterinary Medicine and Science at the University of Nottingham in the UK for approaching The Rottweiler Club to assist with this important research Project.

More information about the research project can be found here in the YouTube video from 2nd Year Student, Shareen Akhtar on her 10 minute talk on Osteosarcoma in Rottweilers at the LASER Show in Essex (apologies for the background noise!). For the latest updates on the research project please download the PDF

|

| ||||||

JLPP (Juvenile Laryngeal Paralysis & Polyneuropathy)

Juvenile Laryngeal Paralysis & Polyneuropathy (JLPP) is a genetic disease that affects the nerves. In affected dogs, JLPP starts with the longest nerves in the body, one of the longest nerves is the one that supplies the muscles of the voice box (larynx) leading to muscle weakness and laryngeal paralysis as the first symptom.

The vocal folds vibrate noisily and can obstruct the flow of air into the lungs when the dog is exercised or when it is hot. The dog may also choke on their food or water or regurgitate, and this can cause pneumonia.

The disease then progresses to the next longest nerves which supply the muscles of the back legs resulting in difficulty getting up and wobbly gait, the hind limbs are followed by the front limbs. Other symptoms include abnormalities in eye development. Symptoms typically start after weaning age.

Trait of Inheritance

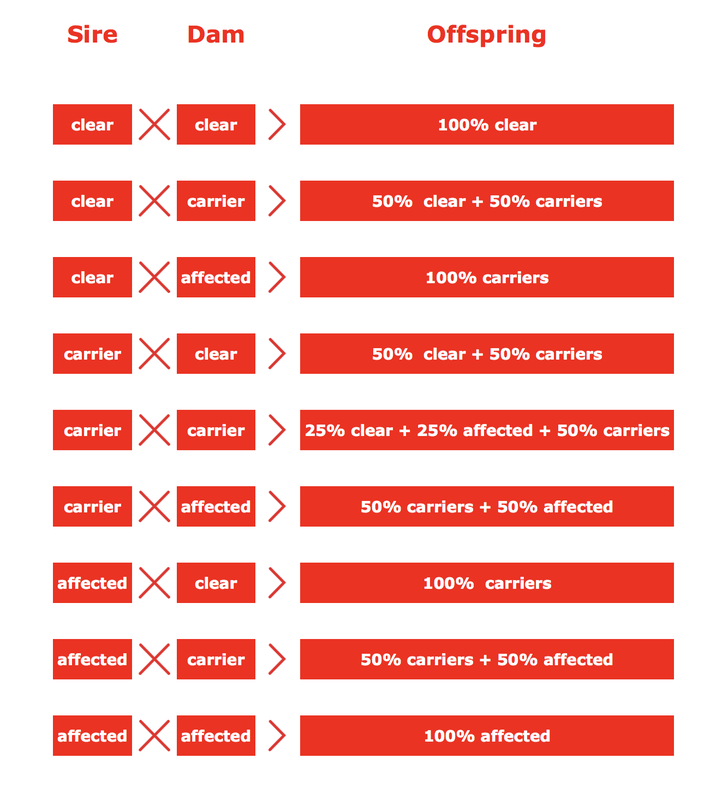

Juvenile Laryngeal Paralysis & Polyneuropathy (JLPP) is inherited as autosomal recessive trait. The test enables breeders to identify their dogs as Clear (N/N), Carriers (N/JLPP), or Affected (JLPP/ JLPP), and this helps breeders to avoid having affected puppies while maintaining the diversity of the gene pool.

Clear

Genotype: N / N [ Homozygous normal ]

The dog is noncarrier of the mutant gene.

The dog will never develop JLPP and therefore it can be bred to any other dog.

Carrier

Genotype: N / JLPP [ Heterozygous ]

The dog carries one copy of the mutant gene and one copy of the normal gene.

The dog will never develop JLPP but since it carries the mutant gene, it can pass it on to its offspring with the probability of 50%. Carriers should only be bred to clear dogs. Avoid breeding carrier to carrier because 25% of their offspring is expected to be affected (see table below)

Affected

Genotype: JLPP / JLPP [ Homozygous mutant ]

The dog carries two copies of the mutant gene and therefore it will pass the mutant gene to its entire offspring.

The dog will develop JLPP and will pass the mutant gene to its entire offspring.

This test is part of the Official UK Kennel Club DNA Testing Scheme in Russian Black Terrier ( RBT ), and Rottweiler.

This article has been reproduced by kind permission of Laboklin (UK)

The vocal folds vibrate noisily and can obstruct the flow of air into the lungs when the dog is exercised or when it is hot. The dog may also choke on their food or water or regurgitate, and this can cause pneumonia.

The disease then progresses to the next longest nerves which supply the muscles of the back legs resulting in difficulty getting up and wobbly gait, the hind limbs are followed by the front limbs. Other symptoms include abnormalities in eye development. Symptoms typically start after weaning age.

Trait of Inheritance

Juvenile Laryngeal Paralysis & Polyneuropathy (JLPP) is inherited as autosomal recessive trait. The test enables breeders to identify their dogs as Clear (N/N), Carriers (N/JLPP), or Affected (JLPP/ JLPP), and this helps breeders to avoid having affected puppies while maintaining the diversity of the gene pool.

Clear

Genotype: N / N [ Homozygous normal ]

The dog is noncarrier of the mutant gene.

The dog will never develop JLPP and therefore it can be bred to any other dog.

Carrier

Genotype: N / JLPP [ Heterozygous ]

The dog carries one copy of the mutant gene and one copy of the normal gene.

The dog will never develop JLPP but since it carries the mutant gene, it can pass it on to its offspring with the probability of 50%. Carriers should only be bred to clear dogs. Avoid breeding carrier to carrier because 25% of their offspring is expected to be affected (see table below)

Affected

Genotype: JLPP / JLPP [ Homozygous mutant ]

The dog carries two copies of the mutant gene and therefore it will pass the mutant gene to its entire offspring.

The dog will develop JLPP and will pass the mutant gene to its entire offspring.

This test is part of the Official UK Kennel Club DNA Testing Scheme in Russian Black Terrier ( RBT ), and Rottweiler.

This article has been reproduced by kind permission of Laboklin (UK)

Wet Eczema

Wet Eczema is very common in Rottweilers and any dog that has a thick undercoat. It can start with a simple flea bite or a nip from another dog, then progresses into a weeping, purulent mass if not dealt with quickly. It spreads! Very quickly. The best remedy is to cut the hair off close to the skin and wash skin regularly with Hibiscrub – at least three or four times a day until a crust is formed and the wound dries out.

Cold Water Tail

Cold-water tail is a condition known throughout the working dog world, but many breeds suffer from it, including Rottweilers. Not a great deal is known about the condition, but it is thought the base of the tail temporarily becomes ‘dead’ by cold water or sitting in the snow. The dog holds out the base of the tail for 4 or 5 inches then the rest hangs limply. This condition is usually only short-lived from approx. 2 to 5 days. Some vets suggest a warm compress on the base of the tail.